Risky business: Naming buildings after New Mexico politicians

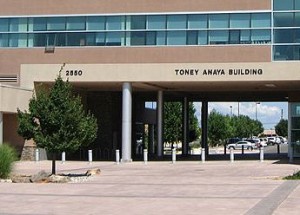

WHAT’S IN A NAME?: A gigantic New Mexico state office building is named after a former governor who just got in big trouble with the Security and Exchange Commission.

By Rob Nikolewski │ New Mexico Watchdog

SANTA FE, N.M. – Former New Mexico Gov. Toney Anaya is awaiting potential financial penalties after settling last week with the Securities and Exchange Commission over fraud charges involving a water company for which Anaya worked.

But while Anaya is the latest in a string of New Mexico political officials who have run afoul of the law, state employees still go to work every day in the sprawling, 100,000-square foot Toney Anaya Building on Cerrillos Road in Santa Fe.

State Sen. Mark Moores, R-Albuquerque, shakes his head.

“We shouldn’t be naming these buildings after politicians,” Moores said. “It’s unseemly for taxpayers to be footing the bill for things like this.”

While not admitting or denying the charges, Anaya agreed to a cease-and-desist order from the SEC and a five-year ban on penny stock offerings. Anaya did not comment on the settlement, but the former Democrat governor and New Mexico attorney general served for two years as chairman and CEO of Natural Blue Resources, which billed itself as an environmentally friendly investment company.

According to the SEC, Anaya hid from investors that the company, in reality, was being run by James Cohen and Joseph Corazzi, who had run afoul of the law in the past.

FACING PENALTIES: Former New Mexico Gov. Toney Anaya has settled with the Securities and Exchange Commission over his role in a water resource company that the SEC said hid vital information from investors.

“Investors in Natural Blue had a right to know who was running the company behind the scenes,” Andrew Ceresney, director of the SEC enforcement division, said in a statement. Anaya “cooperated extensively” in the investigation, the SEC said.

Anaya served as New Mexico’s governor from 1983-87. Former Gov. Bill Richardson named a state office building that houses the Regulation and Licensing Department and the Aging and Long Term Services Department after Anaya in 2004.

“These kind of situations happen when we name buildings after politicians,” Moores said.

The most glaring example happened in southeast Albuquerque, where an elementary school library was named after Manny Aragon, a former New Mexico Senate leader who was convicted in 2008 — and served time in a federal prison — for taking kickbacks.

Parents in southeast Albuquerque complained about library’s name for 5 1/2 years and, in March, the city’s school board voted to have the name erased.

Moores introduced a bill in the 2013 legislative session that would eliminate naming public buildings after elected officials who are currently serving in office. The bill never got out of committee, but Moores said he plans to bring back the legislation for the 2015 session in January.

NO MORE ‘MONUMENTS TO ME’: State Sen. Mark Moores, R-Albuquerque, thinks public buildings should not be named after sitting politicians.

“My constituents are all for it,” Moores said. “They see it as typical behavior by politicians to glorify themselves instead of working for taxpayers.”

Moore’s bill would not erase names of public figures on current structures.

New Mexico Watchdog has cited numerous examples of buildings named after political figures across the state in a series of stories called “Monuments to Me.”

Examples range from massive public edifices — such as the Peter V. Domenici United States Courthouse, named after the Republican and U.S. Senate mainstay before Domenici retired from politics — to a kerfuffle in Taos in 2012; county commissioners voted to name three buildings in Taos County’s new municipal complex after themselves.

The commissioners reversed their decision after residents howled, although the county did order a bronze plaque honoring them for “overseeing” the construction of the complex.

Just three weeks later, the Taos County Clerk had her name inscribed in gold lettering on 55 historical record books as part of project to preserve documents dating back to the 1800s.

“It’s not right (for public officials) to use taxpayers’ money to build monuments to themselves,” Moores said. “Not while they’re in office.”

Other examples across the state include:

* The African American Performing Arts Center in Albuquerque, which opened in 2007 and was rededicated to state Rep. Sheryl Williams Stapleton, D-Albuquerque, by Richardson in 2008. Williams Stapleton has been a state representative since 1995.

* The Ben Luján Gymnasium at Pojoaque High School, named in 1993 to state Rep. Ben Luján, D-Santa Fe County, while he was serving in the Legislature and who later became Speaker of the House. The gymnasium also served as a voting location, which meant that in the 2010 Democratic primary, voters in the area had to go to the Ben Luján Gym to cast their votes either for Luján or his opponent, Carl Trujillo.

* The University of New Mexico Children’s Hospital has a pavilion named after Richardson and his wife, Barbara, while Richardson was still in office. The decision was made in 2004 by the UNM Board of Regents, which was composed of seven members appointed by Richardson.

* The Andy Nuñez Health Department Building in Hatch, named after then-state Rep. Andy Nuñez while he was serving as a Democrat in the Legislature. Nuñez is running this fall to return to the Roundhouse as a Republican.

* State Sen. Howie Morales, D-Silver City, has a baseball stadium named after him in Bayard. Morales used to be a baseball coach at Cobre Consolidated School District.

* Cleveland High School in Rio Rancho is named after Dr. V. Sue Cleveland, who is the superintendent of Rio Rancho Public Schools.

Contact Rob Nikolewski at rnikolewski@watchdog.org and follow him on Twitter @robnikolewski