TIF cost Nebraska $22 million in school dollars

By Deena Winter | Nebraska Watchdog

LINCOLN, Neb. — State lawmakers are considering creating a state division to oversee the use of an urban renewal financing tool that, some say, is being used incorrectly by Nebraska cities — such as those that have declared cornfields blighted.

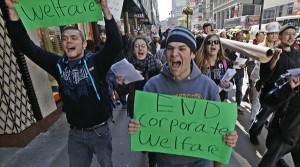

DOLLARS FOR DEVELOPERS: More state oversight of an urban renewal financing tool called TIF is being considered by state lawmakers.

Sen. Al Davis, R-Hyannis, introduced a bill to increase transparency and accountability when tax increment financing is used. TIF takes property tax revenue that would normally be paid by developers and diverts it back into their projects, usually by paying for public infrastructure near the project.

A public hearing was held Tuesday on the LB1095, which would create a state TIF Division to come up with standard processes to ensure cities use TIF properly and uniformly. Developers who use TIF would pay fees to help cover the cost of the new division. An amendment offered Tuesday would also penalize companies that fail to meet their objectives.

Davis said the number of TIF projects in Nebraska has exploded — from 149 in 1996 to 636 in 2012, with 3.5 percent of cities’ land in TIF districts. Its scope has expanded from its original purpose of revitalizing blighted areas to a broad economic development tool, he said.

TIF projects divert money that would otherwise go to other taxing entities – chiefly, school districts, and then the state increases school aid to make up for most of that lost revenue. Analysis by the Revenue Committee’s research analyst, Bill Lock, concluded TIF required the state to increase school aid by $22 million annually.

Davis called that indirect subsidy a “grave concern,” because other property owners shoulder the higher costs for public services that serve the TIF developments. Davis said TIF has a legitimate place in redevelopment but shouldn’t be used as an economic development tool.

Renee Fry, executive director of the OpenSky Policy Institute, called the bill an important step toward improving the transparency of business incentives without limiting TIF’s use. Many applications of the law aren’t meeting statutory requirements, she said.

She cited a study by Jack Dunn of the Progressive Research Institute of Nebraska that found most TIFs have gone into downtown Omaha and benefitted people of means, creating new condos and entertainment complexes that the average “family wage earner can only rarely afford.”

“Poverty downtown has not so much been alleviated as relocated and replaced by gentrification,” Fry said. “North and South Omaha remain relatively untouched.”

In 2012, TIF cost county governments about $8 million in potential tax revenue, community colleges about $2 million and NRDs $900,000, Fry said. Dunn’s 2008-09 study of 37 TIF districts in Omaha found 30 failed to show the project couldn’t have been done without TIF. Under state law, TIF can only be used if a project won’t happen “but for” (without) TIF.

The lack of uniform application of that test leads to questions about whether cities or developers truly benefit, she said. Dunn’s study said TIF projects can subsidize projects that would have happened anyway, shifting costs from the developer to the city and other property tax payers.

The bill was supported by the Nebraska Association of School Boards, Nebraska Council of School Administrators and Nebraska Rural Schools Association. It was opposed by various city officials and the League of Nebraska Municipalities.

Plattsmouth City Administrator Ervin Portis disagreed with Davis’s contention that there’s not enough transparency now, saying TIF projects must go through a cumbersome, complex approval process with multiple public meetings and notices. His bedroom community 20 minutes from Omaha hasn’t had a major commercial development since 1991, he said, and TIF helped the community land a grocery store that now employs 392 people, 87 of them full-time.

Former Omaha City Attorney Ken Bunger said he drafted most of the TIF legislation in the past four decades and negotiated the agreement to lure ConAgra to Omaha with incentives. He said the current law requires more than enough transparency and said decisions should be made locally.

“Nobody’s getting rich on TIF,” he said.

But Sen. Russ Karpisek, D-Wilbur, a former mayor, said when cornfields are being blighted, it’s clear cities aren’t self-policing the program.

“I’m not against TIF, but I think it’s been very much abused,” he said.

Sen. Brad Ashford, D-Omaha, said elected officials need to be clear that the public pays for TIF projects.

““It has exploded,” since the 1970s, he said.

Assistant Bellevue City Administrator Larry Burks said in the development world, the developer with the best return-on-investment lands projects.

“We really have to improve on the developers’ ROI,” he said. “And this is the best tool.”

Nebraska City Administrator Joe Johnson advised lawmakers not to burden cities “who are doing it right.”

Karpisek said the bill doesn’t take away TIF, it just adds oversight.

“Oversight means we lose,” Johnson said.

Jack Cheloha, lobbyist for the city of Omaha, said a 2011 study of TIF in Omaha found most TIF bonds were paid off early and the projects sparked additional growth nearby, making up for 70 percent of the diverted tax revenue.

Sen. Amanda McGill, D-Lincoln, said TIF is cities’ only economic development tool, but a lot of cities are operating outside of their statutory authority.

“I think TIF’s a great tool,” she said, but needs to stay in line with the law. She chairs the Urban Affairs Committee that has the bill.

Contact Deena Winter at deena@nebraskawatchdog.org. Follow Deena on Twitter at @DeenaNEWatchdog

Editor’s note: to subscribe to News Updates from Nebraska Watchdog at no cost, click here.

The post TIF cost Nebraska $22 million in school dollars appeared first on Watchdog.org.