The Data Doesn't Support A "War On Cops"

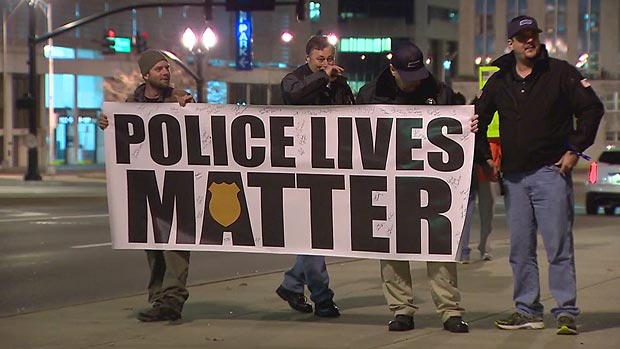

Sparked by protests over officer involved shootings, and now the #BlackLivesMatter movement, many claim that there is a “war on cops” in America right now. But if there is one, it doesn’t seem to be showing up in data.

“A Google news search finds 32,000 results for the phrase ‘war on cops‘ and another 12,100 results for ‘war on police,‘ with sensational headlines like ‘America’s War on Cops Intensifies‘ and [NYPD Commissioner] ‘Bratton Warns of Tough Times Ahead Due to ‘War on Cops’,” writes Professor Mark Perry. “A recent Rasmussen poll found that 58% of likely US voters answered ‘Yes’ to the question ‘Is there a war on police in America today?’and only 27% disagreed.”

But Perry took a look at officer fatality data and found something pretty shocking. “According to data available from the “Officer Down Memorial Page” on the annual number of non-accidental, firearm-related police fatalities, 2015 is on track to be the safest year for law enforcement in the US since 1887,” he writes. “And adjusted for the country’s growing population, the years 2013 and 2015 will be the two safest years for police in US history.”

Here’s Perry’s chart of the data, adjusted to reflect the changing size in the U.S. population:

It would be interesting to put this data in the context not of the overall U.S. population but of the police population. I wonder if the ranks of law enforcement have swelled over the years at a rate faster than the overall U.S. population, and if that context wouldn’t show the decline in officer fatalities to be even more dramatic.

That quibble aside, there are two important points to make about this data.

First, it’s interesting to note the impact America’s prohibitionist policies have had on law enforcement safety. Perry has America’s Prohibition Era marked on the chart, but notice there’s another spike in officer fatalities in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. That coincides with the rise of the “war on drugs,” which was officially declared by Richard Nixon in 1971.

What’s galling about those correlations is that the cost to America of these prohibitionist policies in not only money but the lives of law enforcement has been enormous, and entirely squandered. Alcohol prohibition was an abject failure, and can anyone really say that the “war on drugs” was a success in the 1970’s? How low would the fatality rate for law enforcement (not to mention the general public) go if we, say, legalized marijuana?

A conversation worth having.

Second, many (including this observer) have become concerned about about the militarization of civilian police forces to the point where many law enforcement officers, to hear them talk, no longer seem to consider themselves civilians. One could argue that this decline in police fatalities, though, is a result of the better equipment law enforcement agencies have been able to access. Body armor, armored vehicles, enhanced surveillance and monitoring equipment, and better weapons no doubt had an impact.

If so, great, but as Perry writes, “the downward trend in the annual number of firearm-related police fatalities for more than a quarter century does seem to run counter to the perceptions of the public and media that it’s more dangerous today for American’s police officers than ever before,” an argument often used as a justification for making law enforcement even more militaristic.