Study: Only executives get richer in crony capitalism

By M.D. Kittle | Watchdog.org

n what may come as heartbreak for the U.S. lobbying industry, a new study suggests business success or failure has little to do with political connections.

The study, published by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., finds that political activity has no significant effect on the performance of most firms and industries.

Company executives, however, well, that’s a different story.

While lobbying on behalf of industry has soared amid increasing government handouts and sweetheart crony capitalism deals, the study’s authors, economists Russell Sobel and Rachel Graefe-Anderson, find little evidence that firms or their shareholders benefit.

“We do, however, find a robust and significant positive relationship between political activity and executive compensation,” the economists state. “Therefore, while industry and firm-level performance are not robustly related to ‘cronyism,’ executive compensation is — suggesting that any benefits gained from corporate political activity are largely captured by firm executives.”

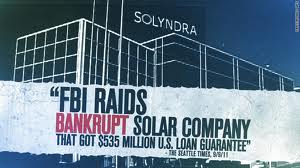

EXHIBIT A: Solyndra may be the most egregious example of political lobbying doing nothing for companies and investors but fattening the wallets of executives, according to a new study by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

Thanks to big government bailouts such as the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program, the “too-big-to-fail” buyout of bad assets from more than a dozen financial institutions, there’s been a lot of money pushed into the pockets of bonus-grabbing corporate executives.

Add to that $840 billion in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 for so-called “shovel-ready” government-fed projects, and you get a better understanding why total expenditures on lobbying the federal government climbed by 25 percent from 2007 to 2010, to $3.5 billion, according to the Mercatus Center study.

“Lobbying by the finance, insurance, and real-estate sector alone has been over $450 million per year since 2008, and the industry is now represented by approximately 2,500 registered federal lobbyists,” the report states.

“In addition to increasing its lobbying activities, the finance, insurance, and real-estate sector has also increased political donations given directly to federal political campaigns,” the study continues. “These donations are made largely through (political action committee) contributions, rising from $287 million during the 2006 election cycle to $503 million during the 2008 elections cycle and $319 million during the 2010 election cycle.”

Political pals and government grants, contracts and bailouts are becoming a bigger part of the American business environment.

The 2011 Inc. 500 list of fastest growing companies contained several firms that received stimulus funding, and many of those companies finished toward the top of the list. An example is Solazyme Inc., the second fastest growing private business on that list. Solazyme received more than $25 million in federal contracts and a grant, which represented more than two-thirds of Solazyme’s annual revenue of $38 million.

“Not surprisingly, Solazyme’s political activities have shown a significant increase at the same time,” the study notes. The company’s lobbying expenditures soared from $20,000 in 2007 and 2008 combined to a total of $232,000 in 2010 and 2011.

And top employees and executives at the publicly held U.S. biotech company made nearly $10,000 in campaign contributions to federal political candidates between 2008 and 2011, according to the study.

A growing portion of critical capital is being diverted from the traditional track of trying to compete in the marketplace into lobbying for political favor, Sobel said.

“When government starts handing out lots of goodies, it makes businesses convert their investments into trying to obtain government goodies,” the visiting professor at the Citadel in Charleston, S.C., told Watchdog.org.

In consequences, companies begin getting lazy looking for government handouts, while hungrier foreign entities eat their lunch.

So what does the company and the average shareholder get out of political connections. Not much, according to the study.

The most glaring example is the now-famous Solyndra Inc., the disastrous alternative energy company failure, once held up by the Obama administration as a positive model of public-private partnerships.

Turns out, not so much.

Solyndra received three stimulus awards totaling $535 million before declaring bankruptcy in 2011.

The company’s lobbying expenditures exploded over four years, rising from $160,000 per year in 2008 and 2009 to $550,000 in both 2010 and 2011, according to the Mercatus Center study.

In reviewing data from across dozens of industries, the economists found profitability overall of firms is not enhanced by political connections, “and firm shareholders do not gain.”

So who does?

The executives running these companies.

The report found a strong correlation between political activity and rising executive compensation.

There are, of course, the extreme examples of execs benefiting while investors lost. Exhibit A: Solyndra.

Right after the solar panel company filed for bankruptcy, the FBI searched the homes of the company’s CEO, Brian Harrison, and the company’s founder, Chris Groney. The searches and subsequent court proceedings uncovered that several top executives at the firm received bonuses ranging from $44,000 to $60,000, after Solyndra pocketed taxpayer money and just months before it filed for bankruptcy.

The study found one notable exception in the political-return-on-investment formula — the banking and finance industries. Influenced by the $450 billion TARP initiative, the sectors show a link between lobbying efforts, firm profitability and executive compensation.

Companies that accepted TARP funds did so with limits on executive compensation.

In general, though, lobbying investments generated little return on investment for most industries examined in the study.

“Whether the rewards are financial or personal, company executives appear to be the main beneficiaries of political connections between firms and the federal government,” the economists write. “We find little evidence that these benefits flow to firm owners or shareholders, suggesting that the rewards are fully expropriated or captured by firm executives.”