Feds install fences to protect endangered mouse, but the fight continues

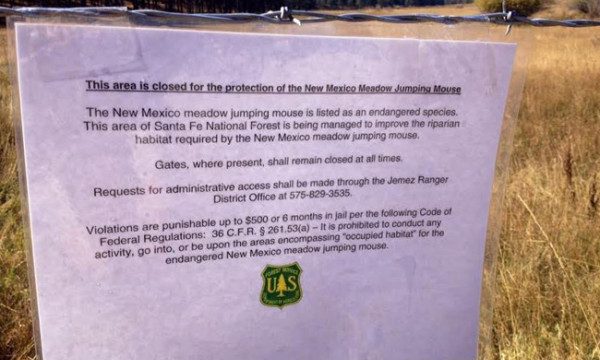

FENCED OUT: The U.S. Forest Service put up barbed wire fencing in a picturesque area in the Santa Fe National Forest to protect the meadow jumping mouse, which has recently been listed as an endangered species.

By Rob Nikolewski │ New Mexico Watchdog

JEMEZ RANGER DISTRICT, N.M. — The fencing is up. The next question is whether the fighting is over.

In reaction to the listing of the meadow jumping mouse as an endangered species, the U.S. Forest Service just completed erecting fences along a creek in New Mexico’s Jemez Mountains. It has become ground zero in a battle between ranchers who have grazed cattle in the meadow for generations and environmentalists who insist the mouse’s habitat must be zealously protected.

“I’m encouraged,” said Bryan Bird, program director at WildEarth Guardians. “I think it’s the right thing to do. I think it’s the reasonable thing to do.”

“We’re not crazy about it but, for now, we can live with it,” said Mike Lucero, a rancher with the San Diego Cattleman’s Association, pointing out his family’s cattle will have access to water above and below the area that’s fenced off. “We can manage around it because we can still get to water.”

FENCED OUT: The U.S. Forest Service put up barbed wire fencing in a picturesque area in the Santa Fe National Forest to protect the meadow jumping mouse, which has recently been listed as an endangered species.

But that doesn’t mean the mouse war — that started when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in June listed the tiny rodent as endangered — is over.

First, the fencing is listed as temporary.

Second, each side has filed lawsuits against the Forest Service.

WildEarth Guardians wants to make sure the feds permanently protect the 0.7-ounce mouse, which has a long tail and hind legs that allow it to hop up to three feet.

The ranchers have filed their own suit, asserting they have taken good care of the creek, called the Rio Cebolla, and that the federal government has overreached and is not following its own environmental policies.

New Mexico Watchdog drove to the area Monday to look at the 4-foot-high barbed wire fencing, completed by the Forest Service just before the cows come down for their annual fall grazing.

The fencing extends about 10 feet to 30 feet from the edges of the creek with signs posted by the Forest Service.

Some 222 acres are closed — including 118 acres of fencing along the Rio Cebolla — near Fenton Lake in northern New Mexico on land often used for hiking, fishing and camping.

Ranching families like Lucero’s own federal grazing permits and have run their cattle along the creek though the old New Mexico land grant system that predates the U.S. Forest Service.

Lucero said the cattle graze and drink in the area one to two weeks in the spring and four to five weeks in the fall after the herd is cut.

A little more than a week ago, a judge turned down the ranchers’ attempts for a temporary restraining order to stop the fencing, but the lawsuit is still going forward in U.S. District Court.

“We’re not going to let it drop as long as the threat continues,” Lucero said.

THE MOUSE THAT ROARED: The battle over protecting the meadow jumping mouse has pitted environmentalistsand ranchers against the U.S. Forest Service.

Environmentalists filed their own lawsuit against the Forest Service, insisting the habitat for the mouse has badly degraded in the three states — New Mexico, Arizona and Colorado — it inhabits.

“It’s important to all of us,” Bird said. “These resources are ours and we need to make sure we’re protecting for them for everybody’s enjoyment, not just the livestock industry … It may seem like a little mouse to people but it’s a big indicator.”

In many ways, the Forest Service is caught in the middle — criticized by environmental groups for what they see as foot-dragging and by ranchers who claim the agency too often sides with environmentalists for fear of litigation.

“That’s always kind of my litmus test,” said Garrett VeneKlasen, executive director of the New Mexico Wildlife Federation, an organization based in Albuquerque that advocates for hunting, fishing and the outdoors. “If the people on the far sides are pissed off, it means the Forest Service did its job.”

Documents released by the agency say the fencing order is a “short-term special closure” that will stay in effect for one year, “until (an) environmental analysis is conducted ” and “consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service can be concluded.” Click here to read the Forest Service documents.

“We need more studies on the area and will work in consultation with the Fish and Wildlife, as well as the permittees, to find a solution that protects the mouse,” Forest Service spokeswoman Donna Nemeth told the Albuquerque Journal. “In the meantime, we have to take protective measures to protect the habitat.”

In addition, the Forest Service has closed off a portion of the San Antonio Campground, a popular recreation spot a few miles from the Rio Cebolla, to protect the mouse’s habitat.